The Calculus Affair

The Calculus Affair (1956) or “how scientific inventions can serve humanity without being coveted by military powers”, in the tense climate of the Cold War. This new adventure takes Tintin back to Syldavia and Borduria. After inventing an ultrasound machine, Professor Calculus is kidnapped. Jolyon Wagg, an insurance sales rep, makes his entrance in this story, and will prove to be a constant nuisance. A thrilling chase, surprises, old friends getting back together, headlong fights... all this for a stake in what seems to be limited to an ordinary umbrella. This is probably the most “detective-like” story.

Test your knowledge

+

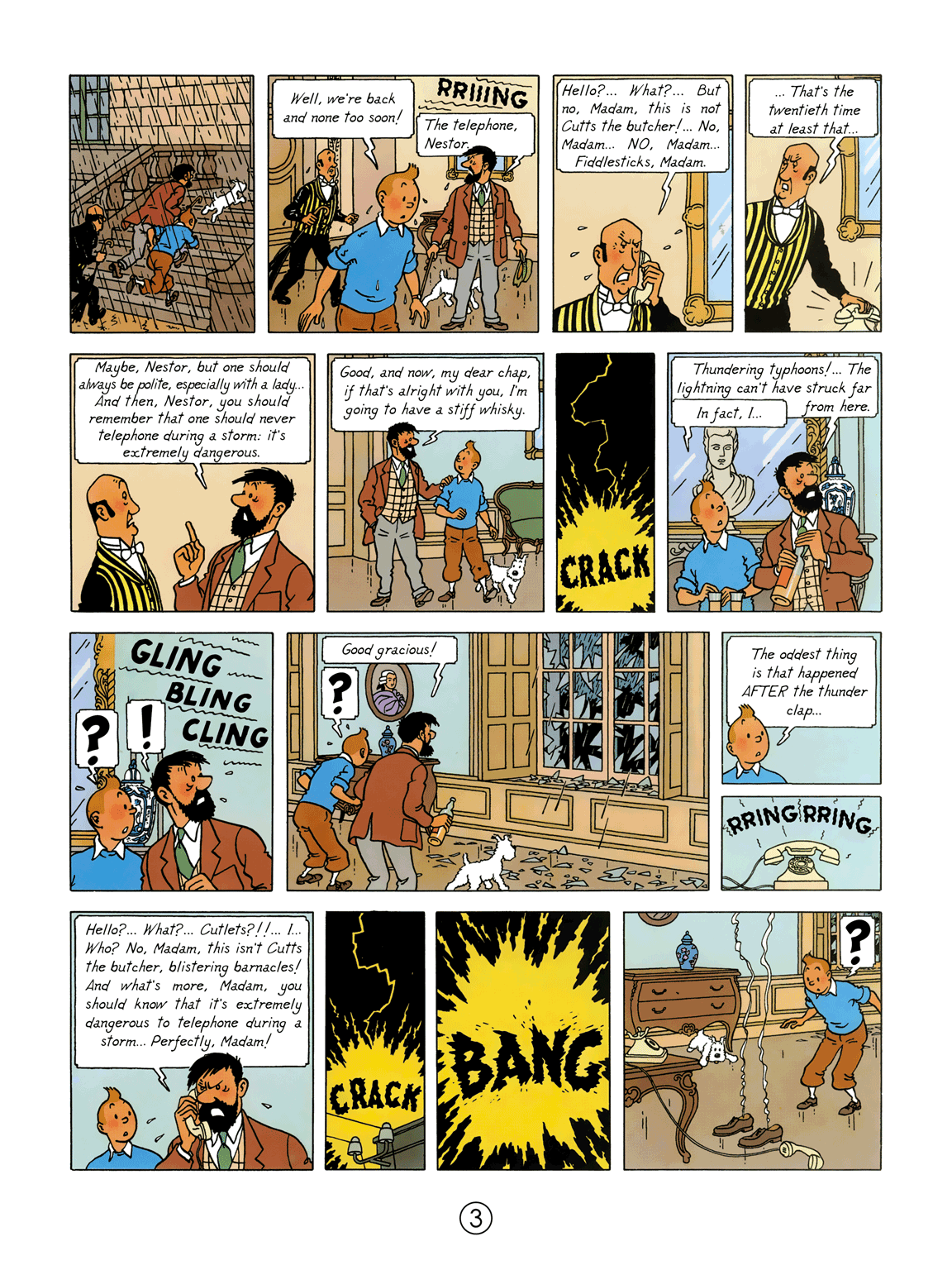

A smashed up cover

At the time that The Calculus Affair appeared as a serial in Tintin magazine, Hergé suggested to his publisher that the cover image should be overlaid with plastic, “specifically mica, placed on top of the drawing itself... in other words, a transparent sheet giving the illusion of glass,” as he explained in a letter dated 11 January 1956. The publisher wasn’t keen on this creative idea and readers would have to be content with the artist’s drawing of a broken window.

Downtown Manhattan in the line of fire

On page 51 of the album, we see a dignitary of the bordering army demonstrating the destructive force of Calculus’ invention. On a television screen appear the skyscrapers of a very American-style city.

This is the symbolic target of the Bordurian aggressors. The similarities with 9/11, a modern-day attack that has also made a lasting impression, are striking. Hergé was keenly aware of the serious problems facing humanity in the twentieth century.

A sticky joke

Following the explosion at Professor Topolino's house, an injured Captain Haddock leaves hospital done up with sticking plasters, one of them on the bridge of his nose. This is the start of the longest running joke in all of Hergé's series. Not only, on page 45, does the plaster make its way through no fewer than 17 frames (the page itself contains 24), but it reappears in 8 frames on page 46. Following its Swiss odyssey, the little piece of sticky bandage crosses over into Borduria on page 47 (4 frames), before being seen again for the last time on page 49.

... and a person who is hard to get rid of

He was going to be called Crampon (in French), but he ended up being called Wagg. Jolyon Wagg bursts into Marlinspike Hall on page 5 and from that moment on, he makes a point of making life hell for Captain Haddock and his friends. Wagg represents everything that Hergé found distasteful in a human being: he is over-familiar, inconsiderate and a master of imposing himself on others. He is also a coward: rumours of a chicken pox epidemic are enough (finally) to rout Wagg and his family.

On another note: at one point in the story, Hergé gives a sly nod to another cartoon hero. Topolino, the name of Calculus' Swiss correspondent in Nyon, means Mickey Mouse in Italian.

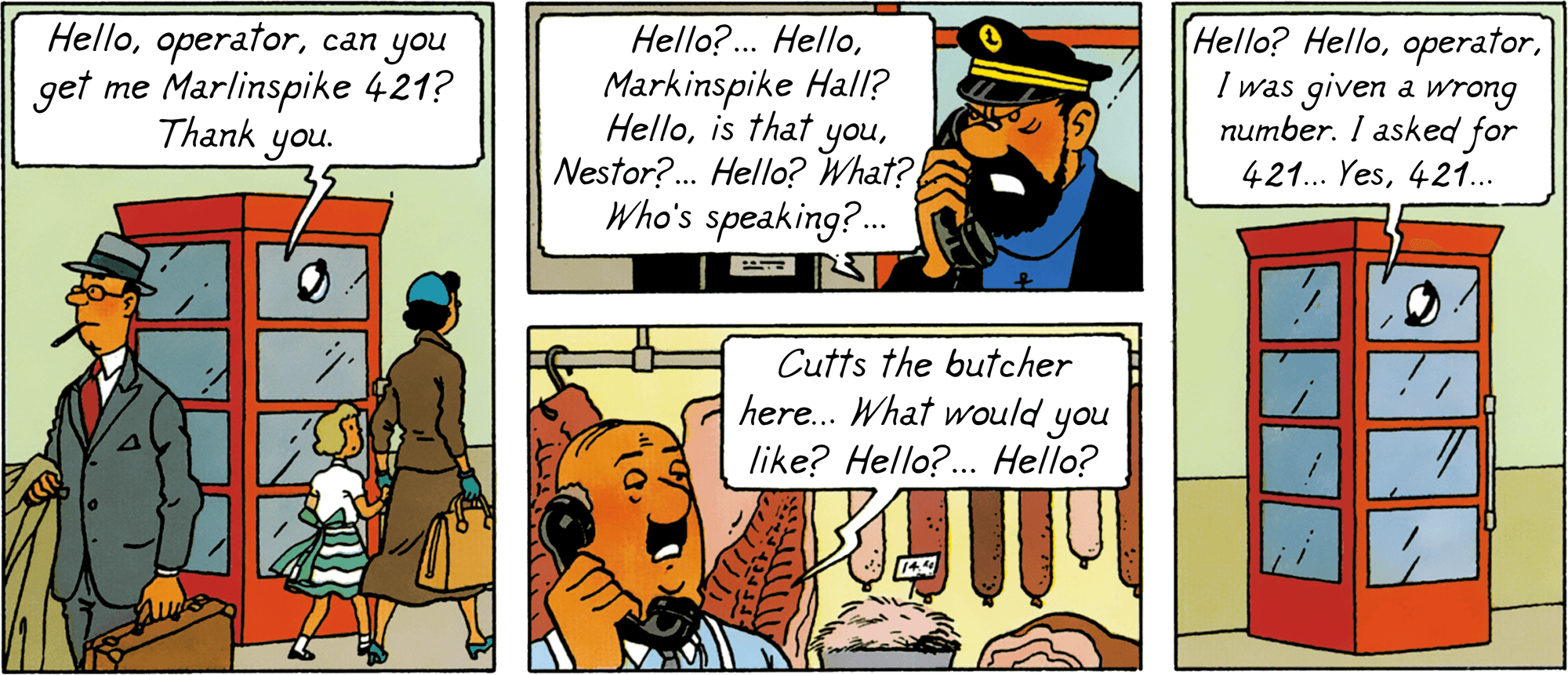

Number 412, 421 or 431?

Hergé moved to Céroux-Mousty in Walloon Brabant (Belgium) at the start of the 1950s, and his new telephone number was 412. Of course it was Hergé who gave Moulinsart number 421, and Cutts (Sanzot in French) the butcher number 431.

The artist himself had been on the receiving end of wrong numbers, and he used these mistakes as jokes in several of his stories.

The key to a hotel full of memories

When they arrive in Geneva, Calculus, and then Tintin and Haddock, lodge at the Hotel Cornavin. Since the album was published in 1956, this establishment has been renovated several times, but nevertheless it still exists. Room 122 (the room Calculus stayed in) was originally situated on the fourth floor just as in the book, but has since had its number changed.

At the insistence of fans of Hergé, the management of the hotel decided to give another room the number 122. Unfortunately, this kind gesture has led to the key to room 122 at Hotel Cornavin going missing on a regular basis, lifted as a trophy by over-fanatical Tintin fans.

The historic town of Nyon

The route which the taxi takes as it drives Tintin to Professor Topolino's house in Nyon, still exists. It has changed, but in 1953 it looked the way Hergé drew it in the story. Today, it's not as easy to steer a vehicle into Lake Leman (page 20). The villa at 57A on the Route de Saint-Cergue in Nyon was recently put up for sale but, in reality, it has never been blown apart by an explosion.

© Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2023

The fire brigades of Nyon keep preciously their rescue vehicle that Hergé represented in the smallest detail, as he made all his sketches and did his research on the spot.

Moustaches everywhere

Upon their arrival in Szohôd (derived from the Bruxellois word "zo-ot", meaning "mad, crazy"), the capital of Borduria, Tintin and Haddock are put up at the Hotel Snôrr. Flemish and Dutch readers understand that "snor" means "moustache". There are moustaches everywhere in Szohôd; on statues and the radiators of official cars, all in honour of the Bordurian dictator, Marshal Kûrvi-Tasch.

This is a clear allusion to the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, the "man of steel" (1879 - 1953). On page 47 of The Calculus Affair, the pose of a statue of Kûrvi-Tasch appears to have been based on official Stalinist imagery.

The era of spies and gadgets

In 1954, at the time The Calculus Affair was published as a serial in Tintin magazine, James Bond was one year old. Ian Fleming’s (1908 - 1964) first novel, Casino Royale, which introduced secret agent 007 to the world, appeared in 1953.

He would popularise the use of all sorts of gadgetry in the intriguing world of espionage during the Cold War era, but it's plain to see that Calculus was the true pioneer in the domain of gadgets and contraptions.